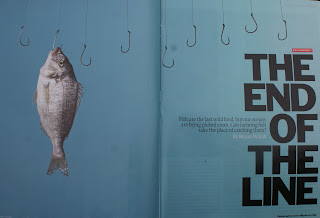

The cover story of Time Magazine this week asks the question, "Can farmed fish feed the world?" Bryan Walsh makes the case for the future of integrated aquaculture, but it sounds better than it really is. It seems ironic to me that he uses the same title as Charles Clover's 2004 novel The End of the Line: How Overfishing is Changing the World and What we Eat. In Walsh's version, farmed seafood is the latest chapter in human control of the natural world. In Clover's version, modern technology and a growing population have wiped out world seafood stocks faster than we knew they were there. Can they both be right?

The cover story of Time Magazine this week asks the question, "Can farmed fish feed the world?" Bryan Walsh makes the case for the future of integrated aquaculture, but it sounds better than it really is. It seems ironic to me that he uses the same title as Charles Clover's 2004 novel The End of the Line: How Overfishing is Changing the World and What we Eat. In Walsh's version, farmed seafood is the latest chapter in human control of the natural world. In Clover's version, modern technology and a growing population have wiped out world seafood stocks faster than we knew they were there. Can they both be right?Introducing Aquaculture

There is no question that seven billion people eating seafood cannot be satiated by the natural world. In Charles Clover's book, he first talks about the total collapse of the cod population in the once bountiful waters of Newfoundland. He then makes a nearly decisive case for the total collapse of bluefin tuna within the next decade. However, the limits of wild seafood fishing are already being supplemented. People around the world are already eating more farmed fish than they realize. As the techniques and efficiency improve, some of it actually tastes good, too. Over 90% of Atlantic Salmon is farmed, over 1.4 million tons annually, and more than 40% of the shrimp consumed globally is farmed.

Basic Math Skills

If there is one glaring hole in Bryan Walsh's optimism, the math doesn't add up. The United Nations says that food production must increase by 100% in the next 40 years to keep up with current demand. That is a startling statistic for seafood. The studies of professor Daniel Pauly are featured in Clover's book, where he finds that global seafood harvest is several years past its peak. That means next year, we will have less wild seafood than this year. However, even in the best possible examples, it takes 2 pounds of wild fish, ground up and fed to farmed fish, and in the end you only get 1 pound of farmed fish, which leaves the ocean at a net loss. So, as Josh Goldman, founder of Australis Aquaculture observes, "the question of what the fish will eat is central to aquaculture. We can't grow on the back of small forage fish." Indeed, since the more realistic conversion rate is 5 pounds of wild fish to produce 1 pound of farmed fish.

Just Add Water

Clearly, the big question is "Can aquaculture technology develop fast enough to keep up with demand?" It will certainly not be able to do so without using resources from the wild. We are learning rapidly which fish are effectively farmed, such as barramundi, tilapia and carp. They have good conversion ratios and their habitat can be effectively simulated in integrated aquaculture systems. Ultimately, the question will be answered by economics. For example, when I started my culinary career, fish like skate, monkfish and black cod were very affordable because they were relatively abundant and underutilized, selling for eight dollars a pound wholesale. Now, fifteen years later, those numbers have doubled. If that trend continues, in 2025, wild salmon could cost $40 a pound at the retail counter. Most Americans will not be able to afford that. In Bryan Walsh's closing arguments, he concludes "if we're all going to survive and thrive in a crowded world, we'll need to cultivate the seas just as we do the land. If we do it right, aquaculture can be one more step toward saving ourselves." Let's hope that step is taken in stride.