wasabi

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Ideas in Food

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

How Wine Became Modern

Saturday, November 13, 2010

What to do with a Medlar?

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Chestnuts, Le Pain Des Pauvres

Soupe au Potiron et aux Chataignes

Puree de Chataignes au Cognac

Trim the venison leg and tie the muscle groups with butcher's twine and season with salt and pepper. Cover the venisoon with milk and marinate overnight. Set the oven at 325 degrees. Drain and dry the venison and sear the meats in a pan to achieve some caramelization. Place the meats in a roasting pan. Peel the pears and toss them in a bowl with a little butter and cinnamon, and add them to the pan. Baste the meats with beurre montee, melted butter emulsified with a little water. Baste and rotate the meat as it cooks, and roast for 20 to 30 minutes depending on the size of the roasts. When the roast reaches medium rare, allow the meat to rest before slicing. Slice thinly against the grain of the muscle, and spread the slices over chestnut puree, on a platter surrounded by the roasted pears.

The Sake Professional Course

Sunday, October 10, 2010

An Introduction to Sake (Part One)

The best rice for brewing sake has a high starch content at its core. In fact, it is too starchy for human consumption. There are over one hundred varieties of rice in use today, some with formidable names like gohyakumangoku, tamazakae, miyama nishiki, and the most widely used yamada nishiki. The climate in Japan varies from region to region, and different varieties grow in these different climates. However, unlike wine, sake is not categorized by rice varietal, but by the amount of polishing the rice undergoes. By milling away the outer layers, which contain the bran, fats and proteins, the brewer reaches a more abundant layer of pure starch.

The polished rice is then washed and soaked in very exacting times, often with a stopwatch in hand. The size of the milled rice grain will affect the soaking time, so that the steaming of the rice can be as consistent as possible. This process is called gentei kyusui, "limited water absorption." The steaming is also carefully monitored, since overcooked rice will ferment too quickly for flavor development, and undercooked rice will only ferment on the outside.

A small portion of the steamed rice is inoculated with a special mold called koji. It takes about two days to complete the inoculation, which then resembles puffed rice with an aroma of roasted chestnuts. This miraculous mold is not a dark mildew, but rather a fragrant white mold that will later break down the starch molecules of the rice, and convert them into glucose, a process known as saccharification. Koji also provides its own unique flavor and aroma to the sake.

Once the koji is made, sake brewing can begin by making a yeast starter called shubo, colloquially known as moto. Shubo means "sake mother." It is formed by combining koji, water, steamed rice and yeast. In the modern sokujo method, lactic acid is added to hasten the development of the shubo. It creates a sour, high acid environment that inhibits the development of unwanted bacteria and wild yeasts. The koji begins to make the mash thick and sweet. the shubo is ready in about two weeks. The old-fashioned yamahai and kimoto methods allow the natural development of lactic acid, which acquires flavor from ambient yeasts and bacteria, and takes twice as long to develop shubo.

Friday, October 1, 2010

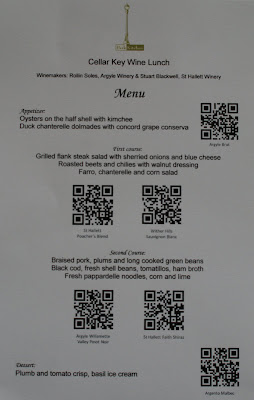

Interactive Bar Codes reach America

.jpg) These 2d codes are like a traditional (1d) bar code, but it has URL's embedded into it. Anyone who has a cell phone with a camera and internet access can utilize the interactive content. In this case, you can learn about Argyle Winery, their products and winemaking principles, see a video about the vineyard, and suggested pairings for the wines. If this ever catches on in America, the marketing sector should be the first to emerge from the economic crisis! And if we wanted to throw a really tech savvy luncheon, we would have printed these menus with soy based ink and edible paper, so you could eat the menu after surfing the web!

These 2d codes are like a traditional (1d) bar code, but it has URL's embedded into it. Anyone who has a cell phone with a camera and internet access can utilize the interactive content. In this case, you can learn about Argyle Winery, their products and winemaking principles, see a video about the vineyard, and suggested pairings for the wines. If this ever catches on in America, the marketing sector should be the first to emerge from the economic crisis! And if we wanted to throw a really tech savvy luncheon, we would have printed these menus with soy based ink and edible paper, so you could eat the menu after surfing the web!Cheers for Sake Day

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Oregon Chanterelles

Saturday, August 7, 2010

The Chester Story

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

The Things I Love About Switzerland (Part Three)

In May or June, when the snows have melted and the vegetation is lush and verdant, it is time for the migration of the black cows toward their alpine pastures for the hundred days of summer. These cows are called stacha in the Swiss dialect (or herens in French), meaning "to puncture," since they must battle each other to establish the hierarchy of the herd. This festival is called the Stachfascht, and determines which cow will be the queen for the season. Then the cows are groomed and decked with flowers, adorned with exquisitely embroidered straps and bells, and paraded up the mountain. This pageant is known as the alpaufzug (inalpe in French), and is commonly depicted in artworks, and painted on walls and facades of the chalets and farmhouses of Gruyere.

The summer days are spent in the pristine alpine pastures, and the cows are numbered to identify their various owners. My friends in the canton of Der Wallis (Valais), the Treyer family, have a summer cabin in the high Alps, and they often lease their mountain pastures for grazing. The luscious milk produced during these summer days in the high Alps is very rich in butterfat and herbal nuances, and has established the worldwide reputation of Swiss cheeses. In September, as the days grow cooler on the mountain, the herd is brought down before the snows return, and the celebration of alpabzug (desalpe) begins. For their triumphant return into the valleys, the cows are often immaculately groomed for beauty pageants, and twelve foot trumpets are sounded in their honor.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Dew Magic

Now the jars are sitting patiently in the garden, soaking up the sun and the walnut's power. Although San Giovanni wasn't blessing the process this year, I hope I've captured a few drops of the dew magic.

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Setting the Field on Fire

Wednesday, June 23, 2010

Family Traditions

Some of the most precious food memories are connected to family traditions. I remember my grandfather showing me how easy it is to make his favorite apple crisp, the many casseroles surrounding the Thanksgiving day table, and my grandmother's Christmas cookies of all shapes and textures. I recently inherited my grandmother's recipe collection. It is filled with more than Aunt Ruthie's sweet potato casserole, or Wilma's swedish meatballs. Thumbing through her recipes is like remembering every family holiday and every summer picnic. Even more than that, it is like looking into the refrigerator of an era of American cooking. The recipe folders have sections like chicken, hamburger, casseroles and crock-pot favorites. There is a salad section with hardly a trace of lettuce, mostly chunky compositions covered with mayonnaise or cool-whip. The pages are made up of cute little index cards from the kitchen of Betty Graeff, and clippings from magazines and soup labels. As a chef, looking through my grandmother's recipe book is as reminiscent as a family photo album. My grandmother, being as efficient as she was, bound her recipes in a fantastic binder with a folding cover, so you can prop it open on the counter at the recipe you want to use. It's fun enough to read her instructions.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

A Deeper Relationship with Garlic

Curing garlic takes about two weeks in a warm place with good airflow. The softneck garlic varieties are often braided into long, fancy pigtails during this process. If you want to display these garlic braids, you can weave flowers or decorative ribbons into the braid. I don't go that far, but it looks nice when it is well done. After this stage, the garlic is storable for fall and winter use. This is what most Americans use year round, and most of it comes from China. Also coming from China and Korea is the relatively new tradition of fermented garlic, which is now also produced in California, called black garlic. This garlic is cured over a longer time and at a higher temperature, which results in a deep black flesh that tastes of balsamic, tamarind and molasses. The sweetness and potency of the garlic is very concentrated.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Rooftop Gardening

.jpg)

This project was developed by Kevin Cavenaugh, the architect and designer of the Rocket Building, and assisted by Marc Boucher-Colbert of Urban Agriculture Solutions. This rooftop garden is reinforced to transform a normal roof, which can hold 20 to 30 pounds per square foot, to an ecoroof which can support 50 to 60 pounds per square foot. That means the rooftop can withstand the additional weight of 6 to 12 inches of soil bustling with healthy plant life. Sous-chef Greg Smith, on the roof looking northward over Portland's east side from the fourth story rooftop. He's been cooking and gardening with chef Leather Storrs since they were at their old address a few blocks away. Keep up the great work, guys!

Leaves and Rice

Sunday, May 16, 2010

Mycorrhizal Symbiosis

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Modern Cookbooks, Modern Techniques

In 2008, the release of two highly polished cookbooks filled with large, exotic photographs, and promising special online features. Alinea (Ten Speed Press) and Quique Dacosta (Montagud Editores) are both books utilizing modern cooking techniques, sometimes called molecular gastronomy, and both books draw recipes from the famous restaurants of their authors.

Even though I understand the high costs, both ecologically and economically, of printing books with ink and paper, I hope publishers continue to actually print books, even if some, or most of the content moves online. The media business is clearly changing, but I plan to keep my bookshelf.

Scenes from La Boqueria, the Mercat de Sant Josep

The main entrance to La Boqueria from La Rambla. This is one of Europe's largest and most famous covered markets. It's a great place for breakfast starting a day of touring the city, or if you're a chef shopping for the restaurant.

The main entrance to La Boqueria from La Rambla. This is one of Europe's largest and most famous covered markets. It's a great place for breakfast starting a day of touring the city, or if you're a chef shopping for the restaurant. You can order tapas at the bars right inside the market. Most of the foods for sale at the stalls are served up in their simple glory at bars like Pinotxo and ...

You can order tapas at the bars right inside the market. Most of the foods for sale at the stalls are served up in their simple glory at bars like Pinotxo and ...Sunday, April 18, 2010

The Things I Love About Switzerland (Part Two)

Of course, there are other designs for the mandolin. The French model (Matfer) shown is all stainless steel, also with an adjustable blade, and can be folded for storage after use. That's nice enough, except that it's heavy and quite expensive. Then there is the plastic Japanese model (Benriner) that has dominated the professional market because it is small and cheap. It also has an adjustable blade, but the plastic parts tend to bend and perform unevenly with sustained usage. So, if you have the space, for the best performance and the most charm, I recommend the Swiss model.

Cool Tools Modernized

One of my favorite things about cooking in another country is finding these special tools. Yes, their mandolin is cool, but I'd used mandolins before. I was pretty excited to see one of their many specialized waffle irons. This dandy is an electric appliance that makes a pressed cookie like something between a tuile and a Belgian Waffle. The Swiss call these treats bricelets or brezeli, and they can be made either savory or sweet. While they are warm, they can be shaped like a tuile, light and crunchy! You can shape cones or cigars, make tile shapes or just leave them flat. The original waffle irons were pattern-engraved cast-iron plates on the end of long iron handles, so they could be warmed in the fire.

If there is one cookbook author that is universally recognized in Switzerland, it is Betty Bossi. She has collected and published extensive recipes from across the country. Taken as a whole, her works are much like a Swiss Joy of Cooking. I found a nice bricelet recipe, but perused another hour through the culinary repertoire.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

The Things I Love About Switzerland (Part One)

Sunday, March 21, 2010

The Noble Spring Vegetable

Asparagus has a long and proud history. It was cultivated by the ancient Romans, and brought into prominence in the French and Italian aristocracy around the sixteenth century. Today, asparagus retains its noble character, while being available to the everyday citizen. It is a vegetable we love for more than it's own virtue, but what it represents. It announces the end of winter roots, and a new season of colorful vegetables and variety.

Asparagus has a long and proud history. It was cultivated by the ancient Romans, and brought into prominence in the French and Italian aristocracy around the sixteenth century. Today, asparagus retains its noble character, while being available to the everyday citizen. It is a vegetable we love for more than it's own virtue, but what it represents. It announces the end of winter roots, and a new season of colorful vegetables and variety. Sunday, March 14, 2010

The Color Purple

Friday, February 19, 2010

Where the Wild Things Are!

These are the first tastes of spring that nature offers here in the Northwest. With our extensive transportation agriculture, we see the early signs of spring in the grocery store long before they are local, asparagus from Mexico, peas and favas from California. These are often good, but not great. In the days before spring begins in earnest, greatness comes from the little things.

Wednesday, January 6, 2010

A Reason to Love January

When we published our first Ayers Creek Farm calendar in 2005, the text merely identified the various crops shown in the photos. Over the next three years, this simple caption evolved into a short essay about the photo's subject. Last year, we balked at the increasingly formulaic approach of scenic farm pictures, and put together a thematic calendar exploring the various legume crops we grow. This 2010 edition takes us to a level of the farm most people never see.At heart, we are naturalists as well as farmers. No, we are not that type of naturalist; we remain fully clothed on the farm befitting our straight-laced New England upbringing. We grew up with Golden Nature Guides and the nature writing of Jean Henri Fabre, Rachael Carson, Edwin Way Teale and others. In that spirit, this edition of the calendar will provide a glimpse of the natural history of the farm. We will show you life beyond the fruits, grains and vegetables we sell, the non-monetized and usually unseen world of the insects, spiders, slime molds and fungi at Ayers Creek Farm.In The Life of the Ant, the Belgian naturalist and playwright, Maurice Maeterlinck, calls these "pastoral ants." They tend flocks of aphids like sheep, protecting them from predators such as syrphid fly maggots. In exchange, the ants draw honeydew from the aphids to sustain the ant colony. One of the ants on the left has collected some honeydew in its mandibles. The aphids are parthenogenic and viviparous through much of their life, that is, producing live young asexually. Like nested Russian dolls, you can open a large aphid and find smaller ones inside, open one of those and yet smaller ones will be found. They molt periodically to increase in size. These aphids have colonized the husks of late ripening corn ears, rich in available sugar and minerals. The last generation of the season's aphids, winged and sexual, will mate and lay eggs. Some of the pastoral ants collect the aphid eggs and store them in their nests, setting them out the next spring to generate a new flock.

The slime mold, fuligo septica, starts life as individual amoeboid creatures, visible only with a microscope. A chemical stimulus brings the individuals together and they fuse to form a new organism. The slime molds aggregate and sally forth in July and August, moving across the ground consuming yeasts, bacteria and fungi. Their movement is determinant, not random, guided by chemical cues released by their food sources. Research has also shown they develop memories, even keeping track of time, and can navigate mazes, wrinkling some of our measures of intelligence. Despite the name, they are completely unrelated to fungi. In fact, there are three major categories of slime molds that are unrelated to one another. These ephemeral colonies are harmless in every respect. As the food supply dwindles, the slime mold produces spores and collapses.

No, we are not lapsing back into the old plum-in-September formula; the creature upon the violet ovoid is the object of this snapshot. The Pacific Tree Frog, hyla regilla, is found throughout the farm, more often heard than seen. Here one awaits the evening upon a Seneca Prune, over a half-mile from the nearest pond. They need open water only for reproduction. The frogs' coloration is variable, and changes with habitat. Those living in the sweet potatoes assume a distinct purplish hue, while in other crops they are pure green or brown. Less frequently encountered are the Red-Legged Frogs, rana aurora, that live in the canyon bisecting the oak savannah at the heart of the farm.

These are not merely indulgent diversions unfolding like an episode of Planet Earth. At the simplest level, every gardener knows what benefit or harm comes from bugs and critters. Every organic farmer knows that living with these insects and micro-organisms makes up the complex biosymbiosis of a healthy farm, and a way of life that chemicals and fertilizers have not been able to supplant.